- Home

- Joe Treasure

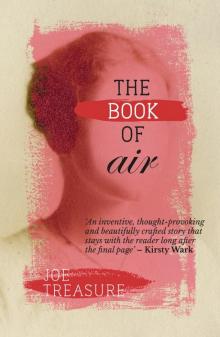

The Book of Air Page 2

The Book of Air Read online

Page 2

I heard the floorboards creaking. Someone moved in the darkness and a low voice made me jump. ‘Soon you won’t be able to call me a boy anymore.’ It was Roland.

I guessed what he meant before he told me.

‘It’s my time,’ he said. ‘The men will come for me tonight.’ He held my hand and I let him.

‘Aren’t you afraid?’

‘Why should I be afraid of what all men must go through if they are to be men?’

I saw him shrug and turn his head away, but I thought he was afraid even so. There were footsteps above us on the landing and he gripped my hand more tightly. I felt his breath on my face and his lips feeling for mine.

‘Don’t,’ I said.

‘Soon, though, Agnes? Say we can talk.’

‘I don’t know. It’ll be different when you’re not a boy.’

‘It’ll be better,’ he said, and I felt his smile.

He pressed against me with his hand on my skirt, and I thought he would feel the ink bottle. So I slipped away from him and out of the Hall, and walked under the stars towards the village. I was at the bridge before my heart had stopped its racketing.

Dear Roland. It’s half a year and more since his voice cracked and a dust of hair settled on his chin. Who noticed but me? Having no parents he is everything and nothing.

I dare say it will be no worse than my own outing just before the break of summer when the women took me up on the moor at dusk. There were two of them. They came dressed as Reeds, veiled in green as Reeds must always be, and stuck about with rushes and meadow flowers. I knew who they were, even so, old neighbours whose men have died, though I knew not to speak to them by name. We call them Reeds, the Mistress says, because it was the name of Jane’s aunt who had to keep her in order when she was young and wild and hadn’t yet learnt her place. The Reeds left me on the moor for a night and a day and a second night to drink mossy water and scavenge for berries. I was hungry, but not as hungry as Jane when she ran away from Rochester’s house because she’d found out he had a wife. It was comforting to me to know that in suffering this I was remembering Jane’s greater suffering. I was lightheaded as the second night came on, and I fancied I could hear Rochester calling to me from far away, but I knew it was just the wind in the bracken. Before dawn I saw the Reeds searching for me to fetch me home. They stirred in the half-light like stunted trees in a gale and I thought the moor had found a new trick to play on me, but I saw soon enough who they were and stood to show myself.

I thought they might feed me, but first they showed me a secret and swore me not to tell and I’ve told no one yet.

And so I became a woman.

I was afraid at first when they came for me at home. I told them I wasn’t ready. But I had bled every month since the last year’s end and had passed my fifteenth year so they knew it was time. And what was it after all but heat and cold and hunger, and a secret to be kept from men and from children.

Jason

I’m still here, Caro. How come I’m still here? It never takes this long. From the sweats to the pit, three days and that’s it. Must be a symptom no one talks about – three days, but the last day feels like weeks, months, while your mind shuts and opens, and every opening hits you like a hangover. You’d tell people, except your head’s on fire and your throat’s closing up. Am I right, Caroline? Was it like that for you?

And I feel so old. I’m forty-four and I feel like an old man. It used to take time to get old.

From the sweats to the pit. The kids took to chanting that in the street. There was a ragged pack of them playing their chasing game the day we got out of London, Simon and me. They were playing as if their life depended on it, and not one of them untouched – jabbing the words at each other. Three days and that’s it.

We hit a road block near Chiswick. Hard men in gas masks, playing at soldiers, keeping the neighbourhood clean. Waving their guns at microbes. The real soldiers had buggered off weeks before. Or keeled over. Same all over London, same everywhere. Containment was the word they used. Didn’t last long. You need police to run a police state.

But they kept us waiting as if they were the real thing. A couple of cars ahead of us, a van behind, all the engines turned off to save petrol. It was quiet enough to hear the hum of the wind. Across the street, a terrace of houses and a pub on the corner, the Green Dragon. You felt the eyes watching through lace curtains and window bars – whoever was left – or just the windows watching.

And all the time I’m thinking, they’ll recognise Simon’s face. They’ll work out who he is. For a couple of days his picture was on the front pages, the TV, all over the internet – not everyone’s forgotten. They’ll ask for ID and see my name and make the connection and shoot us. Or I’ll say I haven’t got any ID and they’ll shoot us anyway.

A woman appeared in a doorway – she was wearing a pale blue sari, some silvery detail along the edge of the fabric, and she was so elegant you’d think nothing could touch her. But the moment she let go of the door and stepped into the street you could see she had the staggers. Her bag hit the pavement and vegetables spilled out – a tight white cabbage, peppers the colour of sunlight, five onions shedding translucent skin, all rolling towards the gutter. See, I was paying attention. We all were. Jesus, Caro, there must have been acres of vegetables rotting all over Kent, all over the south of England, and we were craving the stuff. I wondered if she was buying or selling, but I wasn’t getting out of the car to ask. I was heading west, ready to take my chance on the road. I figured there’d be food enough if we didn’t get knifed picking it. Fresh meat too, walking around on four legs, hens starving in their sheds with no one to let them out.

The van driver wasn’t waiting though. I watched him in the mirror, a big man manoeuvring his belly from behind the steering wheel and out on to the road. He must have been mad or desperate – anyone could see those jokers were itching to use their guns.

Remember what cities used to sound like – sirens and diggers, music blaring from car windows, jet engines. All gone. There was nothing to cushion us from the sudden burst of gunfire and screaming.

It woke Simon. One minute he’s curled up like a cat, next he’s all attention, peering out through the window. He’d seen enough death, God knows, but here was a new twist – the woman on her knees, the loose end of her sari held to the van driver’s neck before he’d even stopped twitching. It took me a moment to register that she wasn’t trying to save his life – it was too late for that. For her too, it was too late. She was dying of what she’d been dying of already. Remarkable the steadiness of her hand, though, as she printed crimson petals on the wall of the pub. Her legs could hardly hold her. I stopped to watch her stoop and rise five or six times, the delicate touches of silk transforming arterial blood into images of poppies and begonias and drooping pomegranates, and a hint of a red pot as she finally sank towards the pavement. The gunmen were dumbstruck, motionless behind their gas masks. It catches you like that, the blessing, every time.

So I watched. But you can’t predict when the urge to live will kick in. Before I’d had time to think, I’d swung the car into a U-turn, skidded up an empty side street, gunfire jabbering behind us, and I was finding a new route to the motorway.

We’d passed the exit for Slough before I realised I was soaked in sweat. The road was abandoned, we had most of a tank of petrol, the Mercedes would take us wherever we wanted. But my heart was racing, panic rising in my chest. A normal reaction, maybe – to the guns, to the murdered driver. But you know when it’s hit you. Once you’ve got the sweats, the rest follows – the staggers, the blessing, the burn, the pit.

Some people think you get it from looking. You watch someone with the blessing, you can’t not watch, and the disease enters through the eyes. That’s the cunning of it. Cunning bollocks. It’s a contagion like any other – it’s carried on the air and you breathe it in.

So what is it, then, this strange opening to impulses and talents never guessed at – a c

onsolation? Or a twist of the knife, a glimpse of what we might have been even at the point of death, to make us all mad with grief?

I saw him last night, Caro – Simon, on his way to bed. It wasn’t a dream. I think it was last night. I know it was evening because of the way the bathroom window across the landing catches the light from the hills. Abigail held him by the hand, keeping him at a safe distance, though he didn’t seem inclined to come any closer. It was nice of her to bring him to see what’s left of me – his Uncle Jason. Simon’s gaze was curious and sad. I tried to wave, but he was gone before I’d worked out how to get my arm from under the bedclothes. I tried to smile, but my face doesn’t always do what I want it to.

He put me in mind of Penny at that age. Whatever Simon got from his father and whatever the world has done to him since, it was my little sister Penny who gave him that look, like the world’s a puzzle and why won’t you tell him the answer. And my mind was invaded by thoughts of Penny until I was in a turmoil of anguish and rage. And I made myself think about you instead, which quelled the rage, though not the anguish.

Death’s become so ordinary I imagine I’m numb to it. Then it catches up with me and I can hardly breathe for the pain. Caro, Caroline, you were really something. Every day we were together I knew I was in luck. And then the luck ran out – mine, yours, everybody’s. I tell myself your death is nothing. Penny’s death, the biggest thing in Simon’s world – nothing. To weep over you, to tear our hair and rend our clothes in grief – an idolatrous obscenity.

But we do it anyway.

When I sang in the hallway, when I cried to you to come back, it was my soul crying to yours. It was reading to you must have put the idea in my head. Reading’s never been my thing, but when you got sick there wasn’t much else I could do. For some of the book you were delirious, but I reckoned you’d read it so often that it didn’t matter, though it was new to me. So I got to know about Jane Eyre, the orphan who grows up to be a governess, and Rochester who’s ready to marry her even though he’s secretly married already, and Rivers the preacher who takes her in when she runs away and nearly starves on the moor. And you were awake enough to correct me when I pronounced Rivers’ first name as if he was a saint. ‘Not Saint John,’ you said, Sinj’n.’ I thought you were raving – something about sin or sinning. But you said it again. ‘Sinj’n, Sinj’n Rivers.’ And then I got it. And I knew I wasn’t wasting my time. So I kept on to the end. I read myself hoarse, while the sun came and went. I read until the lines of text buckled in front of my eyes. Then your temperature dropped and strange things began to happen to you and we had a row – the last thing we did, the last words we spoke before the blessing hit. We both knew you were dying and we were yelling at each other about a made-up story. You could hardly stand, but you were swinging punches at me and kicking my shins with your bare feet and screaming in my face and I was screaming back. It was ugly.

And it was my fault. Entirely and utterly. What was it made me so angry? I felt robbed. It wasn’t a ghost story – I’d worked that out. Yes, all right, weird things go on in the house – ghostly appearances, eerie laughter in the night, Rochester’s bed’s set on fire – but there’s an explanation for all of it – not the drunk servant Grace Pool as Jane thinks at first, but Rochester’s mad wife Bertha locked away upstairs in Grace’s care. Not a ghost story, then, and not a fairy tale full of magical events. Not until right at the end, when Jane’s miles away across the moor with Sinj’n Rivers, and Rochester calls to her and she hears him. The way I saw it, your Charlotte Bronte had pulled a trick. She’d come up with this pathetic piece of magic to sort everything out. I was furious because I was exhausted and I was furious because there was no magic trick to bring you back.

It was three in the morning, a dead hour in a fucked up world, and I had murder in my heart.

I’ve seen couples fight over some stupid things – what kind of shower fittings they want, the colour of the bedroom carpet – but, honestly Caroline, this was the stupidest. Wasn’t it?

Neither of us could bear that you were dying.

Now it’s my turn to die, in this room that we fixed up to be our haven from the world, when there was still a world to return to whenever we liked. It’s pretty much the way it was when you were last here. The door could open and you’d step in from your bathroom across the landing and you’d slip into bed beside me. That photo of you is still there in its silver frame, the one with the silver lilies up the side – you on the front at Brighton windblown and grinning. Your books are still on the shelves either side of the chimney breast – paperbacks mainly, holiday reading – and an old laptop of yours on the desk in the corner.

We used to hear the road from up here, faintly, when there was traffic – delivery vans shifting gears towards the rise, labouring engines, whatever noise got through the filter of trees and across the lawn. Enough to tell us the world was still out there. But never so much that a rising wind wouldn’t drown it, or a herd of cows passing on the moorland road.

First time I brought you here, I was trying to impress you, showing you all this – look at me, lord of the manor, by which I didn’t mean that part of London where I pulled off my property deals, but the real sodding medieval McCoy – and you were impressed, being a wide-eyed middle-class girl from the suburbs. ‘Not actually medieval, of course,’ you said, peering out of the car. ‘Eighteenth century, mainly – though that odd-shaped turret must be earlier.’ I drove us under the arch into the stable yard and you were excited all over again by the stables and outhouses. ‘Lovely Victorian brickwork,’ you said.

All of which I already knew, though I didn’t say so. You’d learned this stuff from books, but I knew it with my hands – the soft surfaces of brick and stone, the crumbling texture of lime mortar, the invisible ripples of the laths behind the plaster, light everywhere, and the settled shape of things because it was all going to be here forever.

It was early summer and the sheep from the farm next door had been let loose on the lawn. We could hear them nibbling below the bedroom window. Sometimes in the dark they sound like old men hacking over their ciggies in pub doorways. Then the crows start up. Then cats and foxes and God knows what. Give me a police siren any day, or a domestic at chucking out time. Not that sleep was what we’d come for. ‘How about double glazing?’ I said, and you said, ‘You mean so we can enjoy the peace and quiet of the countryside?’ And we both laughed. We had a good time, didn’t we, Caro, even though you’d had the best education taxes could buy and I was just an ignorant capitalist.

We were going to have fun fixing this place up. We were going to raise children here. Five at least, I told you. ‘You’ll get two like everyone else and like it,’ you said, but you laughed as if my idea was appealing in a scandalous kind of way. And I wasn’t joking. I wanted a riot of kids. I wanted them tumbling through the woods, climbing the trees, chasing each other up the backstairs and down the big oak staircase, ransacking the attic. I’d be rioting with them – helping them build their tree houses, organising go-kart races on the lawn. Now look at me, Caro. I can hardly move. I’m done for. Put to bed in the turret. It took all their strength to get me up here, Maud and Abigail, with me stumbling between them. They’ll have to carry me all the way down again when my time’s up. Didn’t think of that, did they? They forgot I wouldn’t be walking, wouldn’t be around to dig my own grave.

Agnes

I’ve sent word that I’m sick. I’ve waited all morning to be fetched from my bed and made to answer to the Mistress for what I’ve done. I’m not sick but only in need of sleep. I may be sick if this shaking is a sign of sickness. I’m in need of sleep but cannot sleep. I’m not sick. It’s fear that makes me shake, fear that I shall be punished, fear of the Mistress. What if I’m shut out from the Hall for ever and must find other work? What if I’m never to sit in the study again, or ever to see the Book of Air? My biggest fear is that Sarah will not forgive me.

I wait, but still no one comes.

; I went last night to the Hall when mother had gone to bed. I waited in the stable yard in the shadow of the outhouse wall, crouching against the damp ivy. After a while the Masons came as I knew they would. They came into the yard with a cart, two riding, two walking, their features blackened and muffled. One of the riders stood up in the cart and tapped the window with a bean stake. The curtain moved and I saw the pale blur of Roland’s face behind the glass. Then nothing, except the snorting of the mare and the stirring of branches, until Roland appeared at the kitchen door. He started at the sight of the Masons, but they covered him at once in a black hood and bound his arms. Then they hoisted him up and slung him on the cart like a side of pork, throwing some sacking over him.

If I had turned to the wall and waited for them to go, if I had turned away and they had found me there, I might have suffered only a sharp word. I should have said I was there to save the chickens from the fox. Why not? I might have remembered the chickens scratching in the yard, or the axe left outside to rust in the dew. I might have been restless, called from sleep by the wind, a small slip not worth a flogging. There’s no harm in walking out at night for a purpose. When we hear that scroungers have been seen in the village, mother has me stay out with her sometimes to watch the vegetables and beat pans to scare them off.

The Book of Air

The Book of Air