- Home

- Joe Treasure

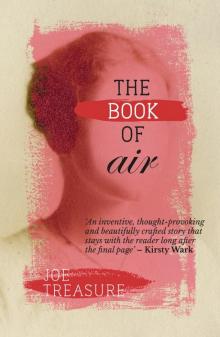

The Book of Air

The Book of Air Read online

The Book

of Air

Joe Treasure

For my father Wilfrid Treasure, craftsman and house builder

And they that shall be of thee shall build the old waste places: thou shalt raise up the foundations of many generations; and thou shalt be called the repairer of the breach, the restorer of paths to dwell in.

(Isaiah 58:12)

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Agnes

Jason

Agnes

Jason

Agnes

Jason

Agnes

Jason

Agnes

Jason

Agnes

Jason

Agnes

Jason

Agnes

Jason

Agnes

Jason

Agnes

Jason

Agnes

Jason

Agnes

Jason

Agnes

Jason

Agnes

Jason

Agnes

Jason

Agnes

Jason

Agnes

Jason

Agnes

Jason

Agnes

Jason

Agnes

Jason

Agnes

Jason

Agnes

Acknowledgements

About Joe Treasure

Copyright

Agnes

This is how I write my name when we’ve made paper and sharpened our pens. Agnes child of Janet. When we copy out our texts in the study. But this is not a text. What is it then?

Our paper in the study is not like this. Not smooth as butter. And not bound like this into a book. A book that is not a book, having no words in it. None until I write them.

Because here are the words. And where do they come from? Out of my head on to the paper.

There are four books. Everyone knows this. Everyone who is not too dull even to learn the Book of Moon when they are six summers old. Four books. The Book of Moon, which is for all the people of the village. The Book of Air, which is for those clever enough to study and with the time to leave off field work. The Book of Windows which is for one or two maybe in a lifetime. The Book of Death which is for no one living, not until the world is soon to end. Four books. What book is this then?

I found it two days past, in an attic at the Hall, behind a big iron box that had a use maybe in the endtime. I was hiding from Roland. He searches for me and wins a kiss. A childish game I thought it was. But since the turn of the year his kisses have grown stronger. His lips press harder on mine, and mine on his until I begin to feel his closeness not only on my mouth, but deep down in my belly.

Should I strike those words out? I would be ashamed for Sarah to see them. But why should I strike out words not meant for her? If I think of Sarah I must strike out all the words. I should suck the ink back off the paper, and leave it as pale and smooth as an onion, which I know can never be done. This book has pulled these thoughts out of my head, and if Sarah saw them she would tell the Mistress who is mean and shrivelled, and the Mistress would have me flogged.

The men were looking to see where the roof leaked and left the ladder up. And so I climbed into the attic. And so I found this book. If the roof hadn’t leaked, if I hadn’t climbed the ladder, the world would still be as it was. If Roland’s kisses hadn’t filled me with longing and made me want to hide so I couldn’t be found. But there I was. And there was the book softened by cobwebs in the grey light. Though I gasped with fear to do it, I slipped it in the pocket of my apron. And down the ladder I crept, and down the staircase, with my eyes closed, as I do sometimes when I imagine myself a person of leisure, trailing my fingers down along the ancient handrail, turning at each flight, until I feel the wooden dog that lies carved on the final post, looking over his foreleg to see who might come in at the front door.

My mother calls me now to bring in wood and boil water for the beans. Our cottage is smoky already from the fire and I have no appetite for supper, but I must go, or see her disappointed in her wilful child. And still my hand keeps moving, dipping the nib, forming the words as I think them. A fifth book. But there are only four books. I think of my dead father, and my gran who once sang me to sleep, and all the dead before them, gone without names, back and back to the endtimers who left us Talgarth Hall and all its treasures, Maud, Mother Abgale, Old Sigh and others long forgotten. So is this the Book of Death? It might well be, such power it has over me.

Jason

I’ve been wandering. I sleep and wake and have difficulty telling the difference.

I was dreaming of the future. I got up from my bed and the place was full of strangers – the staircases and passageways – and no one could see me. I was a ghost in my own house. I opened a door and I was in the orchard. And then you came to me, Caroline, bright and fresh as though you were still alive.

I open my eyes and the world ends all over again.

Was Maud in here again during the night trying to feed me cabbage soup? I hear them down in the kitchen making a racket with pans and knives – Maud and Abigail. They were in the yard earlier, chopping wood and talking to the chickens. Abigail talking. Maud doesn’t talk. I scare her, but she comes anyway. I saw them together on the landing, Maud with an oil lamp, Abigail stroking her hair. She dresses like an old woman, Maud does – headscarf, wellies, layers of cardigans – though she can’t be more than seventeen. Nice enough looking if she ever cracked a smile.

Abigail’s not exactly a stylish dresser, but there’s something about her, the way she holds herself – she knows what she’s worth. And she’s scared of nothing. She put a wet flannel on my face when I was burning up, pressed it to my mouth. A shock of water, ice cold in the throat. When was this? Last night? A week ago? It can’t have been that long because I seem not to be dead yet.

‘I’m sorry, Jason, to see you in this state.’ She spoke in a murmur, looking away, almost as if she was talking to herself. She didn’t want to agitate me, perhaps. At first I couldn’t make my voice work to ask her who she was, but she told me anyway. ‘My name is Abigail.’ An oddly formal way of speaking she has. And she rinsed the flannel and pressed it again to my face.

‘Do you know me?’ I asked her, and she said, ‘This is your house, Talgarth Hall. Your room. We put you here to bed.’ I asked if it was day or night and she said it was early evening and Maud was milking the cows.

‘Whose cows?’

She smiled at that and said, ‘The cows don’t much care whose cows they are.’

Was that one conversation, one facecloth? Or does she come every night?

Maud doesn’t make conversation, but I know it’s her even in the dark. She smells of soup. I swore at her when I first arrived. I think I did. I was in my own fog and whatever I said didn’t come out right. What the fog was she doing in my house? How the fog did she get in? If she knew what was good for her she’d fog off out of here before I called the police. I would’ve been on my face if I hadn’t had the door to hold on to. She backed off up the hall anyway, poor mute Maud, as if I was about to hit her.

Call the police! That’s a laugh. You couldn’t get the police out to deal with squatters even before, even when everything still worked. Before the world caught the sweats. No wonder she kept her distance. What planet had I dropped from?

That’s when I started singing – strange noises I’d never thought of making in my life. You’ll understand this, Caroline, even though I can hardly make sense of it myself. You know how it goes, how the virus takes you. You’ve been through it. Here’s how it went for me. I was of the multitude of the heavenly host.

But I was also myself, and more entirely myself than I’d ever been, with a cry for you, Caro, and for all the dead. Come back! A cry of joy, because for that moment I believed I could reach you. I had to let go of the door because my arms were impelled to move. Only the legs let me down. The impulse was there, shuddering through the joints, but I couldn’t stop the legs from buckling. I had my eye on the newel post at the foot of the stairs – the carved greyhound curled up with its snout under its paw. If I could get that far the world would be saved. It didn’t feel mad. It felt powerful.

I’d wondered what it would be like when it got me, when it reached this stage – the blessing. It’s what everyone thinks about, even if they don’t let on. They lie awake at night, terrified, curious. And then they find out. And that’s them done. Countless times I’ve woken in a panic, stared at the ceiling, heart pounding, wondering how it would take me, how the blessing would feel from the inside. And now I know.

Oh, Caroline, you found out earlier than most.

I was on my knees, but still singing, when the other one came down with a shotgun, turning on our oak staircase – Abigail, hips swaying in her long skirt. And sick as I was, with the barrel pointing at my chest, I felt a shot of adrenalin, God help me – life prodding me in the heart. In the groin. It’s not over yet. You’re not sodding dead yet.

But what about Abigail? Why didn’t she pull the trigger? I’ve asked myself that. Or kick me out, at least? She could see I’d caught it. She would have recognised the signs. Why bring sickness into the house and tuck it up in bed?

They must have found Simon where I’d left him, curled up on the back seat of the Mercedes fast asleep. I know he’s all right because I hear Abigail talking to him. Come down with me, Simon, and I’ll boil you an egg. Her voice drifts up the back stairs from the lower corridor. Take this jug to Maud and help her fetch the water. She’s calm with him and kind and doesn’t ask him questions. You needn’t be scared of the chickens, Simon. They’ll lay you another egg tomorrow.

See, Caroline, she’s talking about the future. Strange word. We used to know what it meant, then suddenly we had no use for it. It’s too late for us, Caro. But if Si remains untouched, I suppose there might be one after all.

Agnes

I’ve been to the Hall today to cook and clean, to fetch in water, keep the wood pile high, feed the geese. I went on as if everything was the same but nothing was the same. Roland came to find me in the kitchen while I was using the grinder – a machine from the endtime with a screw that holds it to the edge of the table and another that grinds the meat when you turn the handle, sending it out in little worms of lean and fat and gristle.

‘That’s a clever thing,’ he said.

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘they were clever who made it.’

‘And when it breaks, what will you use then?’

‘Why should it break?’

‘Not this year or next. Maybe not in your lifetime. But when.’

‘I suppose whoever comes after will have to cut their meat small with a knife.’

‘And when all the knives have been sharpened away to nothing, what then?’

I shrugged. I don’t see the point in thinking about what might happen or not happen that can’t be helped.

‘We dig with metal spades, don’t we Agnes?’

‘Us that have them.’

‘And with wooden ones if not. So which are better?’

I told him I didn’t have time for riddles.

‘The metal ones, of course,’ he said. ‘But do we know how to make them?’

I said if he was just going to talk nonsense he should fetch more wood in, but he stood behind me, holding me at the waist. ‘Too cold outside,’ he said, ‘warmer here with you.’ He mumbled these words against my neck like a child, and I softened towards him. But his hands began to go their different ways, one up one down, until I felt their warmth inside as well as out.

I made to shake him off. For a moment I felt the force of his grip, so I gave him a prod with my elbow and twisted away from him. ‘Your sort can waste the day,’ I said, ‘but us cottagers must work.’ He scowled at me. I had spoken more bitterly than I meant to. He called me a preener. I said, ‘I needn’t listen to you, you’re just a boy.’ And he stalked off to sit in the murk. What had I done to deserve such language but save us both from shame? He might be a child still, but I am not.

They say Roland’s mother died while he was still struggling to be born and there was nothing to be seen of him but his head as purple and wrinkled as a cabbage fit only for pickling. And he had burdened the world for no longer than a week when they found his father face down in the river below the village, his coat snagged in trailing willow branches. He’d slipped from the bank reaching for hazelnuts. So they always told me, though I’ve never seen hazelnuts in February.

So Roland is an orphan and may live at the Hall and pass his time in book learning, except he has no taste for book learning and would rather mope alone. And I who long to master the secrets of the Book of Air must wash his sheets.

Are these thoughts mine? Here they are looking up at me in my own words. Am I angry, then? I am angry with mother sometimes. She is calling me now to feed the pig. I am angry with the pig who lies in straw and grows fat on my peelings. But the pig will have its throat cut to give us pork, and since the day she birthed me mother stands crooked for the pain in her back and hasn’t so much as sneezed without pissing herself, so why should I be angry?

And I have my book, this book which has no words until I write them, which lies open like a meadow on a summer evening for me to lie down in.

Today at the Hall, while I scrubbed and swept, the thought of it burned inside. Before I left the cottage this morning I put it in the box under my bed where I keep my father’s things – the wren he whittled for me when his last sickness began, his best knife, the silver chain his own mother once wore around her neck. The knife is from the endtime and is of great value. Its blades slide open on tiny hidden hinges. The chain is just as old but even more precious because it came from my grandmother who sang to me, but died when I hardly knew what death was. My father gave it to me when it took all his strength to reach it from his pocket. I love these things. But I have never hidden my box with such care as I did today.

And thinking of my book while I worked I felt as though a hole had opened in the sky and I was falling into it. It was all I could do not to tell Roland. I thought of following him to the stables and saying I have a secret, bigger than your father’s death.

But instead I chopped kindling for tomorrow’s fires and listened to the children in the schoolroom chanting from the Book of Moon, and the Mistress telling them that this was how everything will end for each one of them when the last breath rattles from their throats and they are lowered into the pit.

I knew that the older ones were in the study and I chopped faster so that my work would be done and I could join them. I never hear Sarah read from the Book of Air without a leap of joy.

When I reached the study I was in a sweat from chopping wood in spite of the cold. Sarah nodded that I should take my seat between Megan and cousin Annie. Roland was there, having bored himself with brooding. Megan smirked and giggled as I sat down, but Sarah silenced her and encouraged me with a smile.

The study is a temple, Sarah says. But the temple is not a place. Not this room in the Hall, across from the kitchen, with its ancient table smooth and flat for writing on and its big windows with the grass outside where the sheep graze after haymaking. The temple is a state of readiness, a balancing of the pen, a clearing of the mind like a field for planting.

She was explaining again about the four meanings of the Book of Air. That the book itself, and every utterance it contains must be read four times, each time different, to be truly understood. First as the story of Jane for whom everything was new, second as the story of the endtimers and their ancestors from creation to destruction, third as the story of the world and what makes it – fire, water, ear

th and air – and last as the story of our life in the village, how it must be ordered and endured. And that only when all four meanings can be discovered at once and held in balance, as our bodies when we are healthy hold the elements in balance, can we claim to be true readers of the Book.

She read a text for us to write, holding the page like a petal gently between finger and thumb to turn it. It was the story of how Jane met Rochester when his horse slipped on the icy road at dusk while she was out walking, and the spark between them was ignited. Though she had lived in his house for months, working as governess to the orphan child Adele, he had been away all that time and was only just come back. And so she helped him to his feet. And what do we learn from this? That women, though slighter than men, are stronger in character and must lift men up. And that life is a clash of elements, fire and ice, earth and air.

But all the time I was thinking of the ink that I must steal from Sarah’s cupboard and carry from the Hall in the pocket of my skirt. For once I didn’t mind that I must stay behind after the others to dust and sweep. When Sarah’s teaching was done, Roland was first to leave and Megan followed, smirking at me from the doorway because she was free to walk with Roland if she liked but I must stay and work. Annie took my hand. She looked at me in her mournful way and said I should knock on her cottage door when I had time. She lives with her father, Morton, who keeps nine cows and so they live better than most. I said I would, of course, but something dark about Uncle Morton will keep me from knocking. My mother shrinks from him too who has known him all her life. But mother shrinks from everyone.

Sarah had locked away the Book of Air in its cupboard. When we were alone, she asked me was I troubled by anything, and I said no. ‘Your letters are quick and neat,’ she said. ‘I’m glad you make time to come.’ And she gave me such a smile. I glowed with pleasure that she should say such a thing to me.

It was dark when I was done with my cleaning and stood outside in the passageway. The children were long gone from the schoolroom. If the Mistress sat in there alone she sat in silence. I listened for the rocking of her chair on the floorboards but heard nothing. She had gone to bed early, I thought, with her cats, which mean more to her than the people of the village. I felt the weight of the ink against my leg. I have a glass bottle from the endtime that I stole from the kitchen. It has a metal stopper that twists on to the neck so it won’t splash under my skirt but I think everyone must see it when I walk. And I’m afraid if I fall it will break and the stain will seep through.

The Book of Air

The Book of Air