- Home

- Joe Treasure

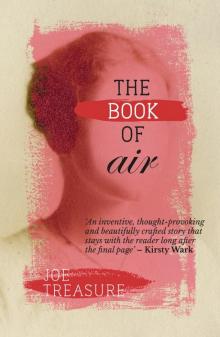

The Book of Air Page 9

The Book of Air Read online

Page 9

We came to a stream and Brendan stopped to let Gideon drink and rest. We sat on fallen stones and ate some bread and boiled pork.

He asked me what I thought about being in the forest and I said I would be afraid to be there alone. He said, ‘Afraid of what?’ and I said, ‘Of scroungers and wild beasts but mainly of the Monk.’ He said, ‘The story of Maud and the Monk is good for a winter evening by the cottage fire’ and I felt foolish then for believing it.

He asked me questions about myself. Do I like cleaning and cooking at the Hall? Am I frightened of the Mistress? Has she beaten me and do I fear to be beaten? Then he asked about Janet. Was she well and happy when I left her? I told him I have never known my mother well or happy since my father took sick, and scarcely before then. I asked him what of his parents and he said he had been an orphan for as long as he could remember and brought up at the Hall when there was another Mistress, long dead now, and Sarah was a child but already more clever in learning than any of them. It moved me to hear her praised, and to know that she understood the Book of Air when she was younger than I am now.

I should not have argued with her at the spring. I let her see me sullen and petulant and am sorry for it.

Later we talked about Jane and the names of Jane inscribed on her Book and whether they are truly her names, or the names of the copiers who made the book, or not names at all but words of some other meaning lost to us. John Murray and Currer Bell and C Bronte with two points over the e, like no other e written. And the strange spelling of Air that Jane uses only of herself and that must never be repeated outside the Book’s green covers.

I asked why the Book of Moon has pictures, which is because it must be understood by everyone chosen for death, which is everyone living. I knew the answer to this, but asked because it comforted me to hear Brendan say it. But when I asked why the Book of Windows can be understood by so few it was Brendan’s turn to be silent. I notice he is reluctant to speak of it. Perhaps it is because he thinks it so far above my understanding, but I think it is because it makes him feel sad in some way. When mother says one of us must feed the pig, and groans with her hand at her back, I go silent sometimes and stare out into the darkness because I would rather be somewhere else where there is no pig to be fed and no Janet, though I don’t know where. This is how Brendan looks when I ask him about the Book of Windows. His sadness stirs me because there is the same restlessness in it. Since we left the village he has seemed younger to me.

He turned then and caught me looking. ‘Trust no one,’ he said.

‘No one, sir?’ I asked him.

‘No one except me.’

‘And Sarah?’

‘Sarah will break your heart. You should find a boy to love.’

‘But not to trust?’

‘A boy with a strong back for digging and strong hands, but gentle when he should be.’

‘And I shouldn’t trust him?’

He didn’t answer, but said, ‘I have brought you where the villagers are afraid to come. Today or tomorrow you will see things you’ll never forget.’ And he spoke to Gideon and we climbed on his back.

The road we travelled on was thick with brambles, but roughly paved along its centre with patches of tar, like the road through the village. We turned off on a track that curved downwards and we were in a vast dried up riverbed. Its sloping banks were thick with trees and underbrush. The wind, finding this opening through the forest, howled along, pushing us forward. Gideon stumbled into fissures and caught his hooves on roots.

After a while the riverbed rose and curved and I saw ahead the slender stilts that lifted it up towards the roof of the forest. It wasn’t a river, then, but an ancient causeway, so wide that you would have to shout to be heard from one side to the other. As we came above the canopy of branches, the sky grew lighter ahead of us, and the sun broke above the trees. I saw in the distance answering flashes of light, stretching into the sky in lines as straight as a ploughed field.

Everyone has heard of the towers of the endtime, and of Old Sigh who flew down from a burning tower to save the Book of Moon. But were they truly a hundred times the height of a man, these towers, and with a thousand windows, as some say? I never believed so. But now I have seen them with my own eyes.

I slept then against Brendan’s back and dreamt of Old Sigh. When I woke, the towers were all around us, sprouting from the forest.

My father once stood on a cliff’s edge. He told me this before he died, that he had run away from the village, westward towards the setting sun. It had been a hard winter and a wet spring and the vegetables were rotting, my father said, and the cattle sick from standing in mud, and the villagers were hungry. He came to the edge of the world and saw the sea a long way down, like a river with only one bank. He told me about the seabirds wheeling and the waves white against the rocks and the feeling that he might topple. Riding among those towers with Brendan I felt that I might topple upwards, tumbling past those windows into the black sky. So many windows, it would take Tal a lifetime and more to patch them up. And how would he climb to reach them?

We stopped by a ruined house and Brendan jumped down from the horse. He stamped on the ground with his boot and it rang with a hollow sound, scattering the birds and sending the forest creatures scuttling. There was a grinding and knocking from underneath. Brendan stepped aside and a door swung upwards and fell back against the ground.

I clung to Gideon’s neck and Brendan told me not to be afraid, it was only Col. I had never seen a scrounger, not to look at, only once or twice a ragged creature running in the shadows. This one called Col looked human I suppose as he climbed out of his hole on his stiff joints, except that his eyes moved about like a dog fearing to be stepped on. Brendan gave him a fresh joint of pork and Col gave Brendan a bag of leaves. ‘Tobacco for the pipe,’ Brendan said. It seemed a poor bargain. I know what labour goes to fattening a pig, and Brendan stood knee-deep in leaves.

I wanted to ask the scrounger if he grew this tobacco himself and where he grew it. But the door was already shut against us and I heard barring and bolting from inside. These scroungers, I thought, steal from us and steal from each other and live in loneliness and fear. And they are as far from planting a crop as I am from flying, and yet here is this tobacco that burns sweeter than any leaf in the village.

I was thinking about this, and thinking what a small mystery it was compared with the size of the forest and the quantity of broken walls among the brambles, and the height of some of them that rose through the trees towards the canopy of winter branches, when Brendan laughed. He must have seen the way I looked about, because he said, ‘Does it frighten you to be so far from the village?’

‘A little.’

‘And excites you a little?’

‘Yes.’

He was in the saddle again and prodding Gideon back on to the path. ‘And does it make you wonder, Agnes?’

‘About what?’

‘About everything. Why did they build so high? Did you see, Agnes, even their roads were made to climb above the forest. I was told as a child that calling was so common among them that they could sit, each in his own tower, and know the thoughts of all the others. Is that possible? Did they sense each other like birds that wheel all one way and then another without warning? Was that how they were killed, do you think, Agnes – not by a fever that lurks in the blood and travels from one body to another in sweat and stale breath, but all at once, in a single convulsion of minds, each agitated beyond endurance by the knowledge of his neighbours’ suffering?’

He looked so young, asking these questions, as young as Roland, and he asked them so eagerly that I laughed, and he laughed too.

I had no answers, but I had my own questions. ‘Were the four books known to them, or were they only for us who came after? And if so, what did they live by? Were the scroungers all villagers once, as they say, and why did they leave to live so desperately? Or were they made to leave, and for what offence?’

And we bo

th laughed again as if we’d witnessed a wedding and were giddy with dancing, though our laughing made no sense.

‘This is where we stay,’ Brendan said. We’d turned in at a doorway wider than any in the village. It led it into a barn high enough for hornbeams to grow tall, and near the frame of the roof pieces of sky where the glass of the endtimers had long ago broken for the wind to blow in. We passed window frames large and square like no windows at the Hall with broken angles of glass at their edges. I saw odd letters carved above them among the ivy and the shadows of other letters. The windows opened on rooms you couldn’t see the end of for the darkness or things growing that love the darkness.

We came to a broken window that was boarded, and a boarded doorway next to it. Brendan climbed down to knock.

‘We’ll eat here,’ he said, ‘and they’ll find us a bed. They call it the O.’

We heard bolts grinding and the door opened. A scrounger looked out at us all smiles, and there were more scroungers inside. Brendan took me by the hand and pulled me in. He pointed at me and said my name and people said, ‘Ho there.’ He pointed at the man who stood by the door and said, ‘This is Trevor.’ Then he pointed at a girl and said, ‘And this is Trevor’s girl, Dell.’ It seemed strange for Brendan to be naming people as though they were just that day from their mothers’ wombs but no one else found it strange because they laughed or smiled and made space for us to sit.

To the back of the room there was a window with no glass and thick bars across it, but the light came mostly from higher up where parts of the roof and walls were missing.

The girl called Dell gave me a cup to hold and filled it from a jug. I’d say she was my age or more, but not a woman yet because her hair was loose and unscarfed. We sat, me and Brendan and Trevor and more scroungers. We sat on chairs, some of wood, some iron, some cushioned with the stuffing spilling out of them, and everyone was talking and Dell filled everyone’s cups. Across the room a man sang. He worked with his hands at a curved box and I heard the notes of his song and other notes that rose from his fingers.

Brendan gave Trevor a sack of eggs and a paper of butter and a loaf and he passed them to Dell, all the time laughing and talking. I saw Brendan hand something directly to Dell – a delicate cup no larger than a goose egg with flowers marked on it, a treasure from his shelves, and I saw her blush and stare sideways before slipping it in her apron and turn back to her work, and Brendan turn the other way to laugh at something Trevor had said. For a while it was as if there was no one in the room but Brendan nodding and smiling in his place and Dell in every other place with her jug. Then I put the cup out of my mind and the room filled up again with talking.

Sometimes the scroungers talked to me or Brendan and sometimes to each other, but I could make no sense of what they said. I wondered if this was French they were speaking or German that Jane learned to speak. But after a while there were words I knew like friends that walk at night from the shadow of a tree.

When I had emptied my cup, Trevor spoke to Dell and she would have filled it again, but I asked for water instead for fear of getting drunk. I was drunk already, I think, on the strangeness of everything. Trevor nodded at me, holding his own brimming mug in the air between us, and said, ‘Here’s licking a chew kid,’ and I thought lick and chew must be his words for drinking. But he said it again when Dell filled his mug, and this time I heard ‘Here’s luck and achoo kid’ as if he meant to bring luck by sneezing.

When it began to grow dark, Trevor said something to Dell. She put her finger to the wall, and lamps hanging from the ceiling flickered and glowed like little moons. Trevor saw that I was startled to see them work without oil or tallow. He leant towards me and said it was the Jane Writer. I felt suddenly warm to him, to think that Jane was with us. I know Jane is in everything and everything in Jane, but I felt I had left the Book of Air a long way behind, and it comforted me to meet it again so unexpectedly.

I said the words back at him – ‘Jane Writer’ – and he smiled and nodded, his face shining with pleasure.

‘Here though,’ he said, ‘I’ll show you.’ He rose, not quite steady on his feet, and led me out into the big room where we walked among the trees and undergrowth. There was a noise like a swarm of bees. We moved towards it, and it was louder, like cartwheels on a dry road. I was a little frightened to be here in the dark with a scrounger, and the mystery of the Jane Writer ahead of us. He unlocked a door and I was almost deafened with the sound. I don’t know what I expected to see. Not this monstrous yellow beetle that squatted, shaking and growling, on the floor. Holding Trevor’s arm, I edged back and eyed the thing from behind his shoulder.

‘It can’t bite,’ he said with a laugh. ‘It’s a machine is all it is. Drinks like buggery, mind.’ He chained up the door again and he led me back the way he’d come. ‘Dell and I keep the old girl going with petrol,’ he said. ‘From the underground tanks. Not everyone’s got the lungs to suck it out. Or would know what to do with it if they did.’

It was only later I understood what this might have to do with Jane. We’d eaten the meat and vegetables Dell had cooked up on the fire, and Trevor said, ‘Time for the pitchers.’ The others made a clatter then with their mugs and started calling out, ‘pitchers, pitchers’. I thought at first it was more drink they wanted. But there was no need to shout for that with the jug passing round so freely.

The people stood, those not too drunk to stand, those who weren’t sleeping, and followed Trevor through a doorway. Dell went round with a tray, gathering mugs and dishes. I waited to see what Brendan would do, if he would stay with Dell. I felt a pang of fear that he would. But he followed Trevor and the others, so I caught up with him and asked him what these pitchers were and hadn’t there been enough drinking for one night.

He said. ‘It’s the pictures. Stay close by me and say nothing until you’ve seen them.’

There are pictures in the Hall and every page of the Book of Moon is a picture, but there was excitement in Brendan’s voice and I knew I was going to see another wonderful thing.

Trevor led us through abandoned rooms, some no more than high walls standing among the trees. We climbed a long metal staircase and walked down a narrow twisting corridor until the walls opened into a sloping room where the seats faced all one way. The others knew to sit without being told. Brendan took my hand. ‘Sit here,’ he said, ‘beside me.’

We sat in darkness with only a few stars visible among the highest branches and heard a noise behind us like insects buzzing. In front, where there had been a wall, blank except for the cracks, there was light, and against the light there were words, people’s names that came and went quicker than I could read, quicker by far than anyone could write. I wondered who these people were. Then where the names had been I saw sky, bright but cold as moonlight, and I had no more questions because I was dumb inside as well as out. There were buildings and people walking, and everything sharply shadowed, but pale where the moon touched it. It was as though a huge window was thrown open and I was pulled from my seat to lean out impossibly. Men walked with hats like soup dishes or flowerpots. I seemed to fall in among them and float.

And all this time a noise like the bellowing of cows late for milking and the wailing of the wind in a chimney and the thunderous sound of galloping horses, but not quite like any of these. And not like women wailing at a burial, either, or singing at seed time. It turned my insides to milk, this noise, and churned them into butter.

The men were dressed in white like at a wedding. One of them ran from me, turning with fear as though I meant to do him harm. There was a crack like a metal nail struck with a hammer and the man fell.

I seemed to be with him in the street, and then inside a house grander even than the Hall. I turned back to see if he needed help but could see only Brendan beside me and others, the light stirring on their faces like moths. I felt my eyes pulled back to the strangers through the window.

But my hand reached for Brendan’s hand and gripped

it hard. It was a comfort in that darkness to feel it so large and strong.

When they took their hats off, the men were sleek-headed like otters and with hairless chins, and pale as if they never saw the sun. They sat with women at tables. The women turned their heads and their ears sparkled. They grew huge until the space was filled up with their faces. Their mouths moved and sounds came like the chirping of sparrows or the croaking of mating frogs.

And I knew that this was not now or here. These were no scroungers beyond the wall. This was a glimpse of the world of the endtimers and I was in the presence of some great power that lingered after them. We had the Book of Air, but Trevor and the scroungers had the Jane Writer. I remembered how Jane as a schoolgirl longed for a power of vision which might reach the busy world, towns, regions full of life, heard of but never seen. Was this the fulfilment of her longing? Was this how she had taught the endtimers to call to each other at a distance? My mind, in turmoil, settled again on the visions and I forgot to think, forgot that I was sitting with Trevor and Brendan and only watched the people move and shrink and loom again in front of me.

Out of all these faces, some became familiar. A man with hooded eyes like a lizard whose lips hardly moved when he spoke, a woman more beautiful than anything I can think of even with an upturned wash bowl on her head, but so pale I thought she might faint. And I began to recognise words. Someone spoke of drinking and they filled their glasses and drank. There was talk of a ring, and a ring passed across a table. A man sat at a desk, his hands busy at his work. He was in charge, always sitting while the others came and went. I could see he was more important than anyone. His eyes were white. His face was round and dark like an eggplant. He turned from his work, though his hands never stopped, and his mouth opened and he sang a lullaby. A kiss is still a kiss, a sigh is just a sigh. Tears came into the woman’s eyes and shone in the light from the moon. Later when the lizard man heard the song, he rested his head on his arms. I ached to live in this hall and have that great round face hush me to sleep.

The Book of Air

The Book of Air