- Home

- Joe Treasure

The Book of Air Page 6

The Book of Air Read online

Page 6

‘My wallet.’

There’s silence while we all take this in. Abigail looks at me, puzzled.

Aleksy is the first to speak. ‘You wanted to order pizza?’

‘I’ll help you search for it,’ I say. Deirdre irritates me but I’m not joining Aleksy’s gang. ‘Why don’t we start in your bedroom and work from there. It can’t have gone far.’

Aleksy’s muttering. ‘Yes certainly, start in bedroom, end in bedroom. Why should I care? Onions must be planted.’

Abigail looks relieved, glad for my help. She stoops again to her sweeping. They’re subtle, these shifts of light across her face, but I begin to find them more eloquent than the gaping and grimacing that most people use to express their feelings.

I lead Deirdre into the hall. Django is kneeling on the floor, breathing into his clarinet. He’s made a start on sorting stuff into piles, boots and shoes in one corner, clothing in another. The monkey’s in the clothes pile with a pair of trousers on its head. Simon is laying leather belts neatly side by side.

I rest my hand on his head as I pass. ‘All right, Si?’

He nods without looking up.

Django raises his head and peers at me through a pair of glasses that make his eyeballs bulge. ‘They’ll be ready for you, Jase,’ he says, ‘when the old eyes begin to go.’ He takes them off and slides them across the floor to a heap of spectacles by the staircase. Seeing Deirdre, he gets up, head tilted in sympathy. He reaches into the inside pocket of his blazer and pulls out a bunch of wild flowers. Yellow petals spill across the oak boards. ‘I picked these for you.’

Deirdre snorts, but takes them and looks pleased.

Abigail has given her the first floor bedroom at the back, overlooking the stable yard, the room with the four-poster bed. There’s a heap of bedding. Clothes spill out of bags and suitcases and trail across the floor.

‘I left it there,’ she says, pointing to the dressing table. Clustered on either side of the mirror are bottles and jars – perfumes, powders, creams. She pushes them around as if to tidy them, and screws a lid on to a jar. ‘I try not to use them.’ I know what she means – there’ll be no more when this lot’s gone. She puts Django’s daisies down on the chest of drawers and looks around. ‘I’m sorry. I know it’s a mess.’ She starts sobbing again.

‘It doesn’t matter. Let’s try and sort this lot out. It’s got to be somewhere. Maybe in a pocket.’

‘But I know it was just there, by the mirror.’

‘Even so. Think of it like an investigation. That’s what my dad used to say if I lost something. Eliminate the suspect from your enquiries – this shelf, or this corner of the room. He liked cop shows – The Bill, Juliet Bravo. Search each place carefully, he used to say, and you won’t have to keep coming back.’

I’d forgotten that about him. It takes me by surprise to be reminded of it now. He was calm and orderly in everything he did, my dad, the same way he’d do a job, dusting thoroughly before opening a paint tin, meticulous about washing brushes.

Now I’ve taken charge, Deirdre doesn’t resist. We straighten the bed. Then we start on the clothes, folding them, or putting them on hangers. She’s got some classy looking stuff. Linen jackets, silk blouses, bits of flimsy underwear lying on the floor like pressed flowers. A surprising number of useless strappy shoes. There are three pairs of riding boots that look as if they’ll keep the weather out, and a couple of waxed jackets.

Deirdre says, ‘When did he die, your dad?’

‘I don’t know – it must be thirty years ago,’ and I shrug because it was an ordinary death, after all.

‘Oh, you must have been young.’ She sits suddenly on the bed. I see the energy go out of her. ‘This is pointless. So many more important things to do. The wallet’s gone, and what use is it to me anyway?’

‘It’s unsettling to lose things.’

‘Yes, but you lose one thing after another that you thought mattered and you’re still alive. And maybe all that matters is water, enough food to keep you from starving, shelter from the cold. But you’re not an animal. You cling to something that tells you that you’re not, not only an animal at least, not yet. We’re the lucky ones, that’s what Abigail says. We made it through. Through to what, though? To wash at a trough without soap. To grub for vegetables in gardens abandoned by the dead. She guards the tinned food like gold. Keeps it locked in the cellar and hangs the key round her neck. Did you know that? Drink your milk, she tells me, as if I’m a child. And I do, though it feels like an assault on my stomach – the richness of it and no substance to fill you up. I’m hungry and bloated all at the same time. Aren’t you?’

‘Not that hungry. There’s something off with my appetite since I was sick.’

‘I’m ravenous. I’m constantly ravenous for something. And even the milk is a luxury we won’t have for long. We don’t even know if the cows will make it through the winter. Have we found them enough hay and silage?’

We sit side by side staring out the window towards the yard and the scrubby hillside.

‘And we’ll never get milk like it again anyway, whatever happens.’

‘Why not?’

‘They’re milkers, Jason. We’re not likely to find a Friesian bull round here. The only bull we’ve found so far is a Welsh Black. Maybe there’s a Hereford somewhere, or a Charolais, but we wouldn’t want a Charolais.’

‘Why not?’

‘Too big. Too many birthing problems. Either way, the next generation’s going to be some kind of cross. Better for beef, not so good for milk.’

‘Beef sounds good.’

‘Yes, and there’ll be calves to eat, if the cows are healthy and things go right, and rennet for making cheese. But so much uncertainty. No antibiotics. I’ve never helped a cow in labour. Have you? And next summer we’ll need to make our own hay or they’ll all die anyway before we see another spring.’

The jackdaws are gathering on the stable roof.

‘At least you’ve still got your house, Jason. What have I got?’

‘You’ve got my house too. For as long as you want.’ I’m surprised to hear myself say this.

I’m back sorting bricks. Maud and Deirdre have brought the cows into the yard for milking. The cats appear, one squeezing under the stable door, another padding, lean and furtive, from the kitchen. Someone will put a saucer down for them, or they’ll balance on the rim of a bucket to lap up the cream. No one knows where they came from, what kind of lives they’ve had. They just moved in, like Deirdre and Django and Aleksy. Soon someone will give them names and they’ll be part of the family. It comes to me with a jolt that this isn’t so far off what I imagined. A gathering of people – children, friends, whoever shows up. It’s what this house was going to be for. Like the Jesus bus of my childhood but with indoor plumbing and no Jesus. It was the one thing they got right on the Jesus bus – that there was more to life than mum and dad and two kids watching TV in a semi.

From the age of fourteen I had an idea of how I wanted my life to be and it started with this house. The first time I saw it, it made some claim on me.

The bus was parked on the side of the road and the grown-ups had sent us out to pick blackberries, five or six of us, straggling along the verge. This was a few years after dad died. Three years, it must have been. I had the saucepan. The girls had plastic bags or held their skirts up. I saw the orchard and thought of blackberry and apple pie. For us lot, food wasn’t something that appeared in the fridge by magic. It took effort. Vegetables came out of gardens and allotments. Not ours, obviously, but somebody’s. A few quid for mowing someone’s lawn meant a pack of sausages or a frozen chicken. Some copper piping pulled off a skip had a price if you knew where to take it. We didn’t steal. Stealing was against the Eighth Commandment. Shoplifting was a sin. If you came back with money you hadn’t earned there’d be trouble. It never occurred to us to break into someone’s house, or try the door of a parked car. But a handful of carrots with the mud still on them? All part of God’s b

ounty. No different from mushrooms found growing in a wood. The Lord was providing and we weren’t asking awkward questions. We were townies, travelling on the Jesus bus, in search of the land of Canaan. We knew what derived from man and what derived from nature. Beyond that, subtle distinctions of ownership went over our heads. So the hedge gave us blackberries and, when we scrambled through the hedge, there was a wilderness of apple trees, boughs bending towards us, the sun reaching down through the leaves, and so much fruit we didn’t know where to start.

We spread out but Penny stuck with me. She was a clown when she was young – all grins and scabbed knees – and she’d have followed me anywhere, and I should have given her more time, but she was my kid sister and I thought she was a pain.

There was another girl too. Tiffany. She couldn’t have been more than five – a chubby thing all bundled up in a bigger kid’s jumper. She kept hold of Penny’s skirt and set up a whine. ‘Wait, Pen, wait.’

Penny was saying, ‘We haven’t got all day, Tiff,’ all bossy, as though we had somewhere to get to.

That’s when I saw this house, and people round a table on the lawn. I told the girls to shut it. We’d reached the edge of the orchard. I was reeling. Was it the people that had this effect on me, or the building? Or what the building added to the people – a sense of solidity? I knew about eating outdoors – we did it all the time, as long as it wasn’t too cold or tipping down. But this wasn’t squatting on a kerbstone or huddled on the steps of the bus. These people had real wooden chairs and a wooden table and reached for sandwiches from a china plate. The front door was wide open and the lawn was just another part of the house, a room with invisible walls.

Penny had started kicking the trunk of a tree as though she could make it rain apples. After each kick she’d hop about clutching her foot and muttering, ‘Broody Judas’. She was performing for my benefit, but I couldn’t take my eyes off the house – how rooted it was, nature creeping up its stonework, sending tendrils up the drainpipes and along the sills. And I said, ‘That’s what I want.’

Something in my voice got Penny’s attention. ‘What Jase, what? What d’you want?’

‘That house. I’ll have it an’ all.’

‘You gunna steal it, Jase?’

‘I’m gunna buy it, and I’m gunna live in it. Like those people. And have my tea on the lawn.’

Little Tiffany was staring up at me, awestruck. ‘Can I come?’

‘How do you mean?’

‘When you buy it, Jase, and it’s yours, can I live in it too, with you and Pen? Can I, Jase? Please?’

The two of them looking at me like that, wide-eyed and earnest, made it seem real, like I’d sworn an oath.

Twenty years it took me.

Agnes

After that first talk with Brendan – he tells me I am to call him Brendan – I took my book at night to the river, upstream beyond the orchard. I meant to throw it in. I thought I would never have the strength to shut my mouth about the book and about Brendan too. To keep silent about this to him, and about him to everyone. It made my head turn and turn like the big staircase in the Hall to think of the lies I must tell. For a while I held the book close and felt my heart thumping against it. Then I swung it behind me, meaning to hurl it into the stream. But at that moment a barn owl shrieked and in my surprise I slipped from the bank into the water. I clung to a handful of cow parsley. When I pulled myself out I was covered in mud and wet to the knees, but the book was unspoiled because I had held it safe above my head. I knew then that I would never destroy it.

I went instead to the Grace Pool. The pot was heavy to move and I was afraid to try. I crept away with my thoughts unspoken. I think there is no such place. I was asleep when I lay down in the courtyard with the Reeds, or it was the herbs they dropped in the candle flame that put the idea in my head.

I should have left the book in the attic. It would have lain there for some other person to find, or until it rotted, and no danger would have come to me. I should have left it with the other treasures. One other thing was of great value and beauty, but I wasn’t tempted by it. A black pipe it was, something like the pipes Tal whittles from bamboo shoots to play tunes on, with holes for his fingers, but longer, as long as my arm, and the holes covered with little rings of metal. Some of them moved as I touched, so I was afraid I had broken them. I blew in at the end, but heard only the rush of my own breath. There were other things too. There was a small leather case not much bigger than my hand neatly packed with little tiles of plastic, each a different colour, with words and strange designs. I’ve seen more like these since in the turret, laid out on the shelves beside Brendan’s fireplace. But I left the leather case and the pipe where I found them. Only the book I brought away with me.

How did they make their paper so smooth and pale, with nothing to snag the nib and suck the ink into puddles, and so much of it, sheet after sheet, each one perfect? Sarah has taught us how to scrape the inner bark from willows and mulberries and dry the long threads from hemp stems, grinding them in the pestle with rushes and leaves of iris. We boil rabbit skins for gum. Stirring all this together in clean spring water, we move our hands and wrists this way and that to catch it evenly in the sieve. We press and roll the pulp and let it dry. And so we make paper. All her life Sarah has done this and knows its secrets as well as anyone in the village. And still how calloused our pages are. Our neatest letters send out tendrils, growing bigger than we meant them.

I would write in this book only for the pleasure of making letters.

The day after our first talk, Brendan sent for me to come from the yard where I was feeding the peelings to the geese. And the next day, from the study. He sent the Mistress, who looked over her glasses at me, and spoke as if I was a child caught sniggering in the schoolroom. The other girls looked at me then, Megan breaking into smiles that were less innocent than they looked, Annie pale and anxious. Roland stared at his hands, thinking perhaps that he was the one who should be sent for, not me. Sarah let go of the page she’d been reading and looked hard into my face as if it would tell her why I was wanted where I had never been wanted before. And the next day another message. And each time I climbed to the turret. Sometimes Brendan had a question, about Roland, or about my mother or about how things went on in the village. Sometimes he wanted nothing but to be brought some nettle tea or a piece of bread. Sometimes he’d have me sit by him and talk about Jane, which I always love to do.

One time, as I came down the big oak staircase, trailing my fingers along the handrail, I found Annie sitting at the turn, hugging the shadows.

She said, ‘Is he kind to you, Agnes?’

‘Kind? Why shouldn’t he be kind?’

‘Is he though?’

I shrugged. ‘He’s kind enough.’

She got up on her knees then and gripped my hand until it hurt. ‘They’re not to be trusted.’

‘Who do you mean?’

‘Men. They can’t help themselves.’

I laughed, but only because I felt awkward hearing her say such things. ‘We only talk, Annie.’ I sunk down on my knees beside her. ‘We sit and talk. He asks me about mother sometimes, and about the Book of Air. We talk about calling and how Jane could have heard Rochester from so far away, a day’s journey at least.’

‘Isn’t Sarah’s teaching enough for you?’

I laughed again, because she looked so earnest. ‘Annie,’ I said, ‘we only talk.’ I left her there at the turning of the stairs.

Another day I was sweeping the upper passage and reached the half stairs and there were his boots on the narrow landing and I looked up and there was all of him. And his whole face was a question so deep you’d need a bucket with a long rope to fetch up an answer.

‘You’re here,’ he said.

‘Yes sir.’

‘Before I sent for you.’

‘This is my day to sweep upstairs.’

His strong eye settled on my face. ‘So you didn’t hear me call?’

‘Did you call?’

He peered at me and his weak eye began its dance. ‘Surely, Agnes, a cry vibrated on your startled ear, in your quaking heart, through your spirit?’ He was saying Jane’s words, but making them his own.

‘No sir.’

He smiled and I wondered if he was teasing me. It made me uncomfortable to hear words from the Book of Air so lightly spoken.

That evening as I walked home from the Hall I saw someone standing at the foot of the drive. The gatepost is half buried in ivy and clematis and overhung with oak branches, so I wasn’t sure it was Roland until he reached out towards me and pulled me into the darkness.

He said, ‘What does he want with you?’

‘Nothing. Just to ask me things.’

‘And you do what he asks?’

‘I mean questions. He asks me questions.’

‘All that time alone, reading and thinking, all that time to study the Book of Windows, and he has to send for Agnes to answer his questions?’

‘Only to have someone to talk to. He knows so much more than me. He knows more than anyone.’

‘Does he though?’ The words were little more than breath against my ear. ‘Does he know this?’ Roland kissed me then, and the feel of his lips and his boyish smell were so familiar, and the shape of him so comfortable against me, that I forgot for a moment that we are no longer children to romp in the Hall and snuggle in corners. I would have stayed longer, cushioned in ivy with his mouth against mine if his hands hadn’t gone to work. If they hadn’t known so exactly where I ached. How unfair it seemed to be divided against myself, and Roland risking so little and me so much. I squirmed away from him, catching my skirt and headscarf in branches of blackthorn.

He turned his back and kicked at the undergrowth. ‘I don’t know why you’re so unkind.’

‘You know why,’ I said, pulling the thorny strands from my hair.

‘I know. Brendan has turned your head and made you think you’re too good for the rest of us.’

I looked at him where he stood, proud and angry, hugging himself because I wouldn’t. And I thought, I shall go home and cook supper and write about this is in my book, just as it happened. And I thought, how strange to be here in this exact moment of my life with this boy who likes me, and to be thinking how to hold it in words for no one to read. As if I had taken a step back from this moment to see how it looked, or as if I had wandered outside of myself and had lost my way.

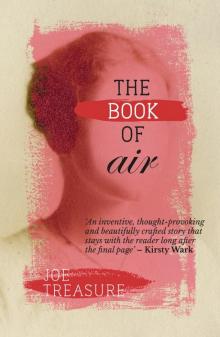

The Book of Air

The Book of Air