- Home

- Joe Treasure

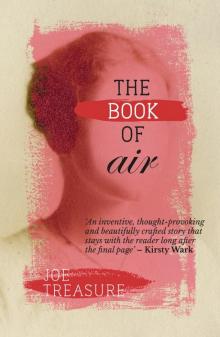

The Book of Air Page 7

The Book of Air Read online

Page 7

Roland had taken something from his pocket and was fiddling with it.

I asked, ‘What is it?’ I was sorry to be fighting. We’d always been such friends.

He shrugged. ‘Just something I found at the Hall.’

‘Let me see.’ It was a machine something like scissors, the two arms hinged like the handles of scissors. They didn’t cross over, though, and become blades, but met in a tangle of notched wheels, all rusted now.

‘What was it for?’

‘They had metal tins with sealed lids. They used this to cut the lids off.’

‘How do you know?’

‘I’ve found some of the tins. You can see where they’ve been cut.’

‘And how did they put the lids back?’

He looked up at me with amusement, as if I’d asked a stupid question and he was glad of it. ‘They didn’t.’

He took the thing from my hand and walked off into the orchard, and I went home to mother and the pig.

And so the days passed. Roland didn’t visit. We passed on the staircase or in the stable yard. But he kept away from the kitchen. The rain held off and I helped with the haymaking, following behind the men as they swung their mowing hooks, to gather the grass. I chopped wood for the fire, fetched water, worked in the kitchen. When I could, I crossed the hallway to the study and listened to Sarah’s teaching and wrote the texts, with the sweet smell of the mown hay coming in at the window. But in every word spoken to me I heard a question. I had become a mystery. I saw Megan grow more giggly with Roland. Annie would come in looking heavy and sullen and say nothing, or come late, or look ill and ask to leave early. Then she stopped home and it was just the three of us. I thought Annie stayed away because she had no one to talk to.

Then a day came when all the villagers were called to the lawn and the Mistress told us that Annie was going to have a child. I blushed to hear this. I was ashamed for her at first, and then for myself. I thought of all the times she had offered to confide in me and I’d thought only of my own trouble.

The Reeds brought her out from the Hall and pushed her to her knees. Ada, who is as thin as a stick, was one of them. The other I didn’t recognise until she set about cutting Annie’s hair. Then I saw it was Miriam, who makes ewe’s cheese and is clever with orphan lambs. She touched Annie gently and we could all see she was sorry for what must be done. She had made a start when Annie tipped forward without a word and was sick into the grass. Miriam waited until the retching stopped, then lifted Annie upright and went on with her cropping, while the Mistress told us that it would be worse for Annie because she would not say who the man was.

‘And why must this girl be punished?’

We all knew to be silent until the Mistress answered her own question.

‘Because we are not cattle and we are not scroungers and we are not vermin, but people of the village. And by the fire that got me I will have you live as though Jane our first Governess listened at every door and watched at every keyhole.’

Meanwhile Miriam worked on until there was nothing left to hide Annie’s skull but a ragged stubble.

I wanted to speak. I burned inside to say this was wrong, that a man had hurt Annie and we must repay her by hurting her again. But the words twisted themselves into a knot in my throat until they made no sense. I glanced at my mother, who stood beside me, but there was a dead look on her face as though she had taken her thoughts elsewhere.

We stood among the racks where the hay was drying, vetch and meadowsweet and grasses of all kinds, yellowing in the sun, while Annie was caned. The Mistress struck her on the hands, so as not to harm the baby, and not as hard as she might have done I thought, but hard enough even so. I looked at Sarah. She was pale, whether with anger or fear I couldn’t tell. I was thinking, what would they do to me if they found my book? I shivered and went hot and felt my insides turn to water. Below by the river a cow was calling to its calf, and I thought how simple to be fed hay and be milked and to have no choices, and I wished there was more noise, enough to drown Annie’s cries. Above me something moved quicker than I could follow. A house martin, I thought, swooping from the eaves. When I looked again I caught a movement of a curtain high under the gable. I felt something like shame to know that Brendan was watching, but for what reason I can’t say.

When the caning was done, the Mistress said, ‘Because she has no man to speak for her, Annie will stay with us at the Hall for a time.’

Annie had sunk to her knees and was hunched over, with one hand on the ground and one on her belly. She looked about to see what this meant. I thought at first it was kind of the Mistress to offer Annie a room, but the whisper among villagers spread a different understanding of her words. I saw the fear grow in Annie’s eyes and felt it rising up inside me, crushing the breath and lifting the hairs on my scalp. Annie wasn’t to live like Roland, lounging at his window above the stable yard, or like Sarah, looking out at bedtime to see the gathered hay pale in the moonlight. She was to be locked in the red room.

‘If she’s good and quiet,’ the Mistress said, ‘we shall keep her only until the baby quickens, and then back home she’ll go, if Morton will take her.’

We all looked at Uncle Morton then. I could see nothing in his face but a sort of impatience to be elsewhere – in his field, perhaps, picking raspberries, not having his time wasted. I think he never learned to be a father, losing his own father so young. While we waited to hear what he might say, there was a disturbance behind me and Daniel pushed between mother and me to stand in the circle. His mouth opened but no words came. Then he said, ‘I’ll…’ but nothing more, while he sniffed and made that grunting noise that always means he’s got a word stuck in his throat.

On the other side of the circle, Tal took a step forward as though he meant to rebuke his son, but the neighbour who stood next to him put a hand on his arm, and he said nothing.

Daniel’s words came out at last in a splutter. ‘I’ll… speak for Annie if she’ll let me.’

There was a commotion and then silence, while we waited to hear what the Mistress would say. Annie fixed her eyes on the ground. The Mistress gave Daniel a sharp look. ‘You’re saying you’ll take her?’

Daniel sniffed twice and said, ‘Yes.’

‘Tomorrow then. In the afternoon, before milking.’

And it was decided.

Next day, when the time came, Daniel looked dazed with excitement. Like all the women, I had woven ragweed in my hair. At first it didn’t feel like a wedding day, there had been so little time to look forward to it. When the men tied Daniel’s blindfold and pushed him into the circle to search for Annie, he played his part well, but Annie shrank from so much attention and could hardly move to avoid his arms. We helped her of course, the women, pushing her this way and that, until at last we allowed her to be caught, but it was a troubled kind of joy I felt, seeing Annie without a hair on her head long enough to tie a ribbon to. She led him still blindfolded to where the Mistress waited. And they were brought face to face in view of the Hall with the sun sinking pale and watery above the orchard.

And so they were married. When Annie loosened Daniel’s blindfold there was such joy in his eyes and he held her with such pride that her own face lit up with pleasure. We all crowded round to hug and kiss her and she wept to find herself so loved, and I wept too. Even the Mistress took her in her arms and whispered some words, perhaps of consolation, and all her shame was washed away. Only Morton seemed unmoved.

Then Daniel led her down across the lawn to the gateway, and across the road and over the bridge to his mother’s cottage and their bridal bed. And we were left to dance, and those too old to dance to cheer themselves with gin. We danced long and wild because it was a day no one would stop us, and Tal played his pipe and Peter beat time on a cow skin drum.

Mother sat for a while to watch. If she ever danced in her life I never saw it. Now any labour hurts her back. Standing hurts her too, and stooping, and sitting too long in one place. Bessie t

alked to her and I saw her smile and was glad. Then Sarah sat by her and took her hand. Roland and Megan went and sat in the shade of a beech tree and seemed very fascinated with each other, so I danced until the trees and the sky ran all together. When I paused to let my head stop turning, I looked for them but they were gone. I went to the spring, splashed water on my face and on my neck and stood while it ran down my back.

Sarah came and knelt beside me to drink. ‘You’re often alone,’ she said.

‘Yes, I suppose I am.’

‘Because you want to be?’

‘Sometimes.’

‘Roland and Megan were here, but I don’t see them now. Why don’t you find them?’

‘I’m not sure they want to be found.’

‘All the more reason.’ She stood wiping the water from her lips with the back of her hand, and then gathering with her fingers the drips on her chin. She saw my confusion. ‘For their sake, I mean,’ she said. ‘Because they’re your friends.’

‘Are they?’

‘Yes. And it would be an act of friendship not to leave them too long alone together. You see what happened to your cousin.’

‘Annie was a different case. Roland and Megan can marry if they want.’

Sarah looked at me closely. ‘And you? Is it what you want?’

I found I was in a state of agitation, to be asked this question, and to have Sarah ask it. For a while we stood saying nothing, watching the villagers on the lawn. Then Sarah spoke again.

‘There are things I should have said to you, Agnes, and I’ve stopped myself.’

‘What things?’

‘The Reader…’

‘What about the Reader? He sends for me and I go. We talk. That’s all. Could I refuse him?’

‘Refuse to talk? No.’

‘What then?’

She hesitated. ‘You know why the man must be led blindfolded to the woman in marriage.’

‘Because Rochester was blinded in the fire but Jane married him anyway.’

‘Yes, and why else? What did Jane mean by telling us that?’

‘That men are made to look about for danger and to see what time is best for planting and for gathering the crops, but in matters of love…’ I stopped, not wanting to talk about love.

‘In matters of love, Agnes, their eyes will mislead them.’

‘But Brendan….’

‘…is a man like other men.’

‘He asks me questions. We talk about the books.’

‘Well then. No harm can come of that.’ I could tell she didn’t mean it. She looked again at the dancers, squinting her eyes against the sun. Then she said, ‘Except that while you talk with Brendan your friends are forgotten.’

‘I’m here now though, aren’t I? And where’s Roland?’

‘Yes, where?’

‘With Megan, not wanting to be found. And I must see to the geese and shut the hens up or the fox will get them.’

‘But first you must find your friends.’

They were the first hard words that had ever passed between us, and I felt very sorry for myself as I walked away from the spring.

I heard Megan laughing as I came close to the stables, not like someone opening her mouth to laugh at a joke, but with a noise in her throat like bubbles rising. I pushed the door open and walked in across the straw, shocked by the sudden darkness and the warm stink of horses. There was a murmur of voices and a rustling of straw or clothing. A horse stirred and snorted. I said Megan’s name because it was her voice I’d heard.

There was a sigh and she rose up from one of the stalls. As my eyes became accustomed to the gloom, I saw she was tying her scarf behind her head, and I saw Roland stand up beside her.

‘Megan, Sarah wants you,’ I said.

‘I bet she doesn’t, though.’

‘She sent me to fetch you. She was drinking at the spring.’

Megan peered at my face to see if I was lying, or to show she didn’t care whether I was lying or not. Then she walked past me, brushing straw from her skirt, and out into the yard.

Roland said, ‘Did you miss me at the dancing?’

I didn’t answer but turned to stroke the horse that had put its head towards me. It was Gideon, who is strong but always gentle.

Roland came close and patted Gideon’s neck. He said, ‘Do you think it was a scrounger was to blame for Annie’s baby, like they say?’

‘Is that what they say? How horrible.’

‘Horrible that they say it, or that she did it?’

‘Do you think it’s true then?’

‘I think the scroungers must be worked off their feet doing all the wicked things they’re blamed for.’

‘So you think it was a villager and she wouldn’t say?’

‘I wonder sometimes if the scroungers even exist.’ I thought he was joking, though he sounded solemn when he said it, but he had rested his head against Gideon’s mane so I couldn’t tell. Then he burst out laughing to see me so confused, and walked away into the yard.

I felt that Brendan was there in the stable before I saw him. He was standing behind me, in the low doorway from the house. He asked if we had all enjoyed ourselves. I thought he must have heard Megan giggling with Roland, or Roland laughing about the scroungers, but saw that it was Annie’s wedding day he meant.

‘Not much,’ I said.

He watched me with his good eye and asked if I was angry.

I shrugged. I might have said no, but found I had enough anger to choke me.

‘Have I offended you, Agnes?’

‘You watched,’ I said.

‘Shouldn’t I watch?’

‘You watched Annie’s flogging from your window.’

‘You watched too,’ he said, ‘and you were closer. I saw you there with the others.’

I couldn’t explain my anger. Why was my watching different from his? So I shut my mouth and scraped at the straw with my foot.

‘Come tomorrow night,’ he said.

‘Come where?’

‘To the Hall. I mean you no harm. Come after dark.’

‘I don’t come to the Hall after dark.’

He looked at me, his weak eye flickering, and I could tell he was thinking of the time I waited under Roland’s window. I had never been punished for spying and he was thinking of that too perhaps. He meant me no harm, but he could do me harm if he wanted. ‘You’re right,’ he said. ‘It would be safer to meet away from the Hall and the village. Meet me in the ruin. Tell no one.’

‘I must tell my mother.’

‘Tell Janet there is work for you at the Hall and you will sleep here for two nights. Dress for a long ride. She knows to say nothing.’

And it was just as Brendan had promised. Janet heard my story and maybe she believed it and maybe she knew it was a lie. She kept her mouth shut anyway, though her face clouded over, and she turned away to stir the soup.

I must go now to the ruin. It’s time. But I am afraid to go. The ruin is a place of danger. Even in daylight I would be afraid. It stands on the margin of the village and the forest. It belongs neither to us nor to the scroungers. People say it was once as grand as the Hall and more beautiful, with windows as colourful as a summer meadow and huge bells that rang all across the valley. The bells are still there, they say, half buried in the ground and overgrown with brambles. This was where the Monk lived.

Everyone knows the story of Maud and the Monk but I don’t know if it’s true.

At the full moon, the Monk would ring the bells and Maud would slip from the Hall at night to meet him and they would dance. But one night she was seen running across the lawn, and next time the bells rang she was locked in the red room. For three nights the bells rang, but Maud didn’t come. And on the fourth night the Monk tore out his own heart and ran away into the forest. Over the years he withered and grew a tail like a rat. And he lives still in the forest, swinging by his tail through the shadows. And they say that if you stand in the ruin when the moon is full, you’ll he

ar the jangle of the bells.

I’m afraid I’ll go to the ruin and Brendan won’t be there. More than ever I feel in need of my father. My heart cries out to him, but he is beyond hearing.

Jason

Someone’s calling my name. I wake up and don’t know where I am. Then the grey shapes settle around me and I’m in my bed in the turret.

I dreamt I had a child. I’d lost her and she was crying to me, crying from across the sea. I was on a ship trying to reach her. The deck tipped up and I was hanging above the water.

‘Jason, are you awake?’

There’s someone standing in the doorway. It’s Deirdre. The others are in other rooms, asleep or doing whatever they do at night. Outside the wind howls and the rain is driven against the glass. Everything else is gone and this is what’s left.

Deirdre carries a lighted candle in one hand, two wine glasses in the other. There’s something insubstantial about her, some softening at the edges that makes me think she isn’t really there. But it’s the candle flame dipping and straightening that sets everything in motion, and a draught rippling the fabric of her dressing gown.

She says, ‘I wanted to thank you for helping me earlier.’

‘We didn’t find the wallet.’

‘But you made me feel better about losing it.’

She steps into the room, shutting the door behind her with her naked foot. So light you’d think the air would lift her. She’s got a bottle under her arm. ‘I’ve always hated losing things.’ She leaves the thought hanging and walks unsteadily to the window. ‘You sleep with the curtains open?’

‘I like to see the sky.’

‘And when you’re not in bed?’

‘Everything else – the orchard, the cottage roofs among the trees.’

The Book of Air

The Book of Air